Edinburgh Plant Sciences – Early Career Researchers Meeting

Edinburgh Plant Sciences – Early Career Researchers Meeting

By Lucas Frungillo1 & Laura Roehrig2

1BBSRC-Discovery Fellow at The University of Edinburgh.

2PhD candidate at The University of Edinburgh & Scotland’s Rural College.

The spectacular and fascinating diversity of plants is evident by their variety in shapes and ability to interact with their physical and living environment. From tiny liverworts to giant trees, every plant species shows unique adaptations that allow survival in a wide range of environmental conditions. Plant scientists investigate how adaptations enable plant development and growth. Dissecting these biological processes will allow engineering of new technologies to maximise our interaction with plants. The development of sustainable strategies for agriculture practices is particularly important to address the food security challenge that is aggravated by the climate crises associated with a growing world population. As collaborations are indispensable to the advancement of science, the Edinburgh Plant Sciences Early Career Researchers organized its first scientific meeting on the 22nd October 2020 to bring together researchers across all disciplines of plant science in the Edinburgh area. The meeting contributed to enhance research capacity and promote new connections between plant scientists by creating a network to get inspired and to inspire others.

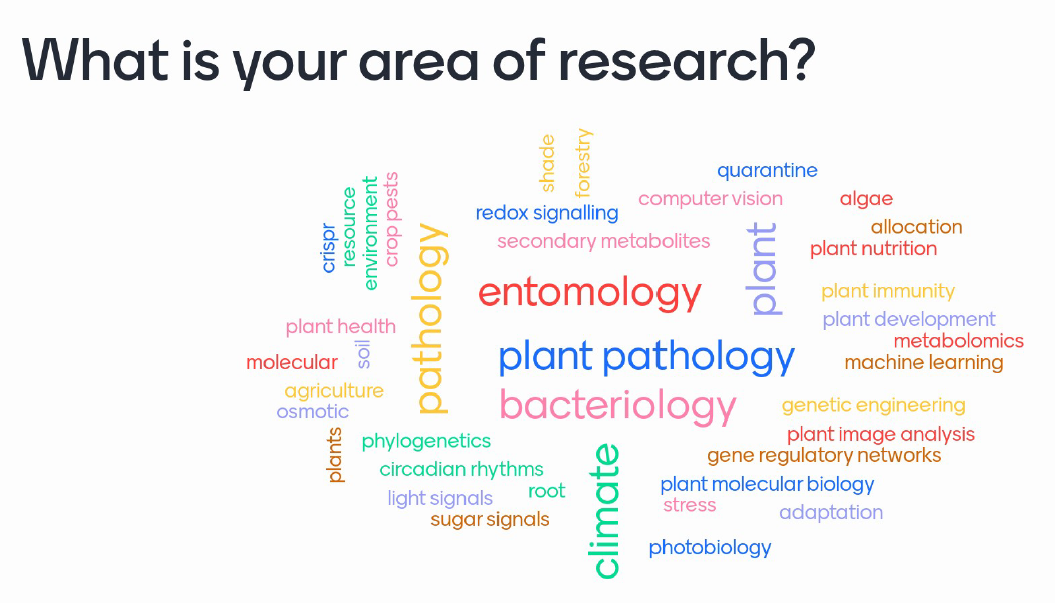

With over 60 attendees from different research areas, the EPS-ECR meeting was an enjoyable and fruitful gathering over Zoom (Fig. 1). The meeting provided a platform for PhD students, postdocs and young PIs to get to know our partner institutes better and present their research. The attendees were warmly welcomed by the EPS-ECR members Dr Valerio Giuffrida (Napier University) and Dr Lucas Frungillo (University of Edinburgh) and the EPS director Dr Alistair McCormick (University of Edinburgh). Their welcome talks were followed by an inspiring talk by Dr Ross Alexander (Heriot Watt University) that explored both career development in plant science and recent findings from his research group. The attendees also had the opportunity to hear about opportunities arising from the EU Green Deal Call by Emma Fenton (UKRI Innovate UK) and Dr Natasha Curley (University of Edinburgh Research Office) and participate in panel sessions on “Transition from PhD to postdoc and from postdoc to PI” (Dr Alistair McCormick, Dr Annis Richardson, Dr Valeio Giuffrida, Dr Lucas Frungillo), “The impact of green spaces and plants on health and the economy” (Prof. Catherine Ward Thompson, Dr Chris Pollard) and “Plant sciences and public engagement” (Dr Janet Paterson, Marie-Anne Robertson, Ninni Nuorti).

Figure 1. Research diversity of EPS-ECR meeting audience using Mentimeter.

The diversity of plant science in the Edinburgh area was showcased by the invited speakers Mavis Osei-Wusu (Heriot Watt University), David Bartholomew (UK Centre for Ecology and Hydrology), Amanda Jones (Napier University & SASA), Dr Aimeric Blaud (Napier University), Yanqian Ding (University of Edinburgh), Laura Roehrig (Scotland’s Rural College), Domen Finzgar (Forest Research & University of Edinburgh), Hazel Wu Huang (Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh), Dr Jason Summer-Kalkun (SASA) and Heather Dunn (Forest Research & University of Oxford).

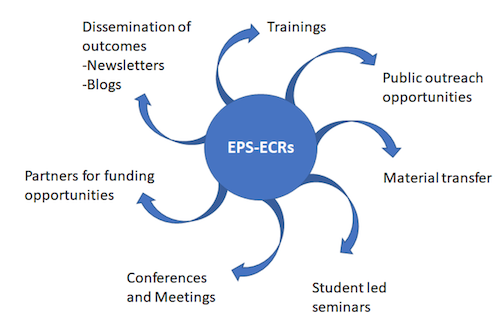

In addition to exploring the breadth of plant research in our partner institutes, the EPS-ECR meeting perfectly represented EPS’ mission to enhance career progression and research capacity, as well as created a channel of communication for the ECR community to develop tailored activities in the future.

Many thanks for the talented attendees, the enthusiastic organizing committee and our sponsors Mentimeter and SULSA! If you want to know more about EPS or get involved, please follow us on Twitter or contact us!

Our attendees